How Wars, Duels and a Few Great Minds Changed Plastic Surgery Forever

Many great strides in medicine have been made in response to urgent need. Plastic surgery is no different—and nothing magnifies the need to repair disfiguring injuries as much as wartime. As Independence Day 2017 approaches, and we prepare to celebrate our freedoms in this country—many of which were secured through wartime sacrifice—I’d like to highlight a few extraordinary milestones in plastic surgery history that happened during war.

Repairing the Aftermath of Dueling in the Renaissance Era

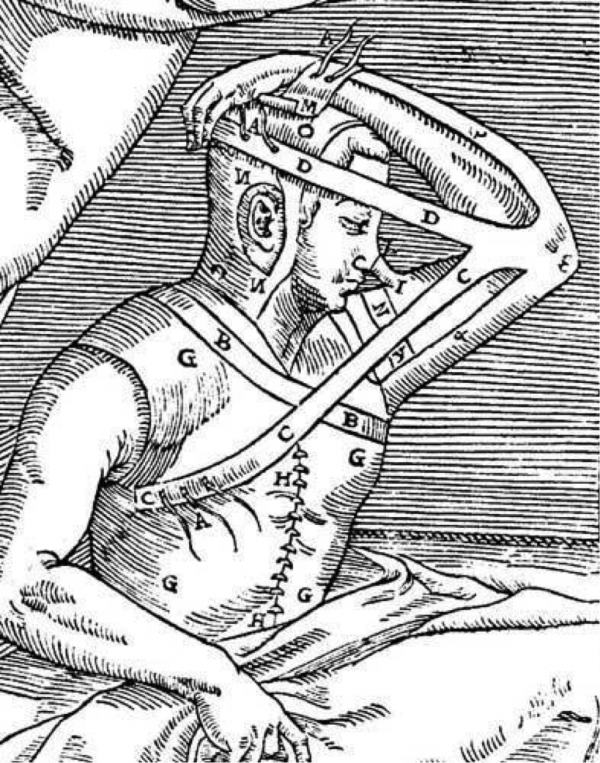

In the west, the link between plastic surgery and military conflict can be traced back as far as the 1500s, when Italian surgeon Gaspare Tagliacozzi (who is also considered the “father of plastic surgery”) developed the “Italian method” for rhinoplasty.

In Renaissance Italy, dueling by rapier (a thin, pointed sword) was quite popular—and quite a few noses got cut off as a result. Tagliacozzi fashioned new noses for patients by grafting tissue from the shoulder to the face over a series of surgeries. This must have been a harrowing feat for patient and surgeon alike, considering there was no anesthesia, and the process involved having your arm strapped to your head for weeks!

World War I: Reconstructing Faces by Trial and Error

Trench warfare in World War I resulted in devastating injuries in large numbers. Trenches protected a soldier’s body, but left the face and head exposed to flying shrapnel. Thousands of men were left disfigured. In response, a doctor from New Zealand, Harold Gillies, set up the first known plastic surgery unit for veterans, ultimately developing a revolutionary technique called the “pedicle tube.”

With the pedicle tube, a section of tissue was partially removed from the arm, leg, or buttock, and rolled into a tube, with one end remaining at the donor site. The other end of this tube was attached higher up on the body, leaving the patient with one body part tethered to another for several weeks while a new blood supply was established. This process was repeated, “walking” up the body, until the donor tissue had a healthy blood supply on the face, and surgery to reshape the tissue into a new nose, cheek or lips could be performed.

The pedicle tube technique may sound crude today, and in truth, Gillies had many patients who did not fare well. However, his efforts laid important groundwork for future advancements in plastic surgery that ultimately led to the much safer, more successful techniques we have today.

If you are curious to learn more, this guide from the BBC tells Gillies’ story in more detail.

The Guinea Pig Club: Giving New Hope to Burn Victims During World War II

By World War II, disfiguring burns caused by aircraft fires presented yet another challenge to plastic surgeons. Building on Gillies’ pedicle tube technique, another New Zealand surgeon, Dr. Archibald McIndoe, was able to restore a remarkably normal appearance for his patients, given the severity of their injuries.

Perhaps what is most remarkable about McIndoe’s work is his insight into the psychological effects of having one’s appearance forever altered. He recognized that treating the patient as a whole person was key to a successful outcome and included social and emotional support in his treatment plans. McIndoe worked hard to encourage patients and believed that their altered appearance was nothing to be ashamed of. He had local families host patients at their homes for dinner, and even had “showgirls” come talk to recovering patients to help buoy their confidence.

Members of the “Guinea Pig Club,” as McIndoe’s patients were affectionately known, often required up to 30 different operations, and spent many months with “trunks” attached to their faces, but long-term, they fared much better than patients from previous eras, largely due to the emotional support they received in addition to reconstructive surgery.

This short video provides a fantastic first-hand account of the difference that McIndoe’s innovative approach made in the lives of wounded veterans:

Valley Forge Hospital: Artists & Plastic Surgeons Join Forces to Improve Lives

WWII plastic surgery history was also made in the U.S.A., at Valley Forge General Hospital in Pennsylvania. Valley Forge opened in 1943 and quickly became known as the place where the best “artificial eyes” were made. Three U.S. Army dentists worked together to develop a prosthetic eye made from acrylic, which could be painted in highly realistic detail (this article shows a great photo as well as an interesting in-depth history of ocular prostheses).

A second fascinating story of art and plastic surgery is that of Virginia McCall, an accomplished artist who volunteered her efforts at Valley Forge. First there to teach art as therapy for recovering patients, McCall was soon called upon to make plaster casts of patients’ faces before surgery, and at various stages of their recovery. She painted these “masks” in meticulous detail, to then be used by plastic surgeons as 3D references during the reconstructive process.

Happy Independence Day to you and your family

Whether you have plans to celebrate July 4th with a family picnic, a quick getaway, or just a relaxing long weekend at home, I encourage you to take time to reflect on the sacrifices made by our armed service members and their civilian supporters throughout the years. Their contributions paved way for the freedoms we enjoy today.

Thank you for this. My late father acquired much of his burn craft at Queen Victoria hospital, Sir Archie’s unit, before being recruited to an academic Plastic Surgery post at Temple University.